A Foray into Foraminifera

We’re on Green Island in Taiwan for the next month to work out how plankton make shells!

Why are we studying plankton?

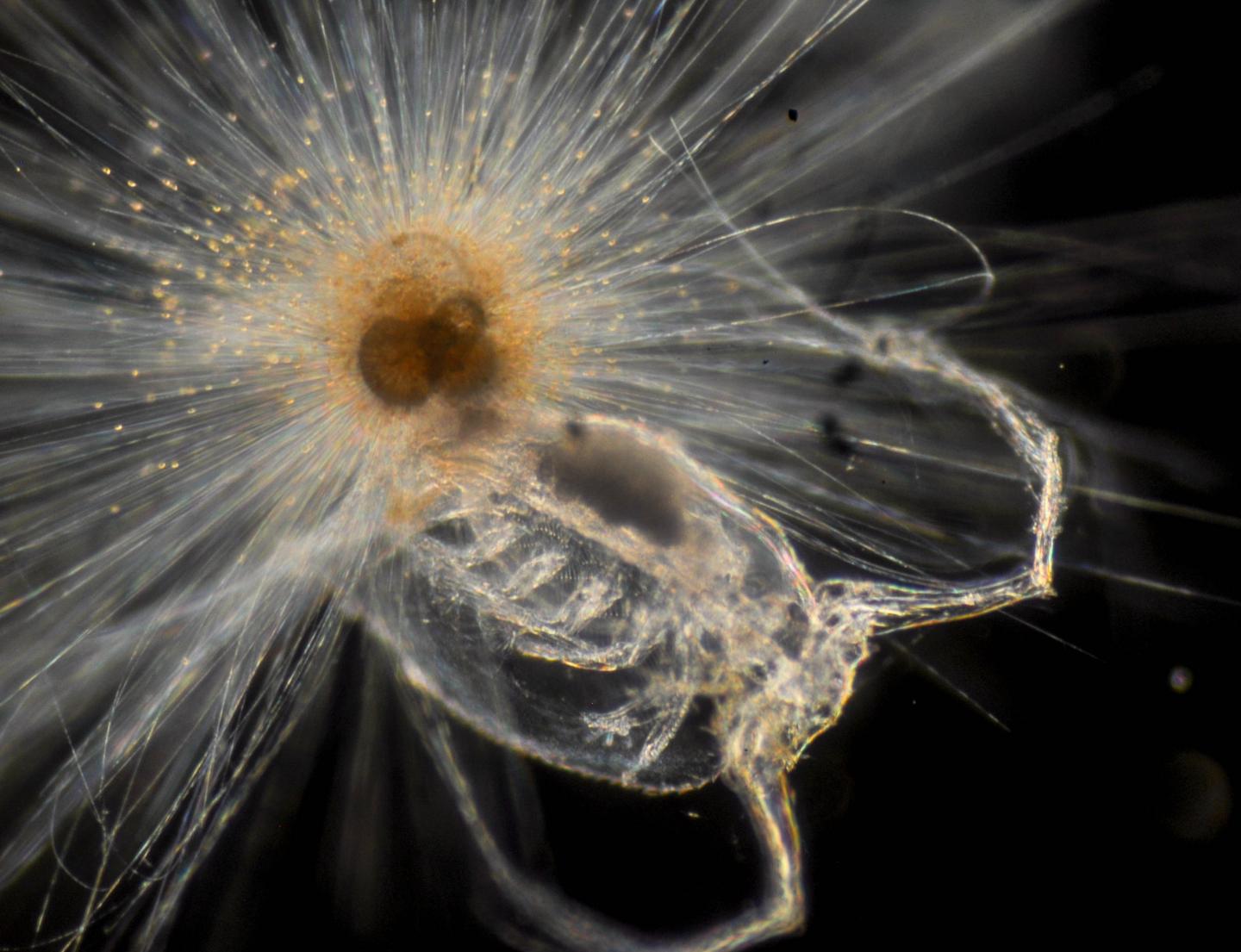

The type of plankton we’re interested in are foraminifera (‘forams’ for short). Forams are single-celled marine organisms, many of which build microscopic shells out of calcium carbonate. Forams are interesting for many reasons - they’re single cells that grow up to several mm in diameter (that’s BIG for a single cell), they have complex life cycles and relationships with symbiotic algae that they ‘farm’ for food, and they can be voracious predators in the microscopic world they inhabit. We’re not worrying too much about all that though - we’re interested in them because they make shells.

The shells made by foram are mostly made from calcium carbonate, and we’re interested in them for two main reasons. When the shells form they remove carbonate (CO32-) from seawater, and when the foram dies this shell sinks to the seafloor where it is buried in the sediments. The formation and burial of these shells plays an important role in the global carbon cycle.

Buried foram shells in the sediments also provide an archive of past ocean conditions. Foram shells contain impurities and imperfections which change depending on the environment that the foram was living in. This means that scientists can dig up foram from ancient marine sediments, and use the properties of these chemical impurities in foram shells to work out what the environment was like when the foram was alive. The chemistry of foram shells provides a ‘proxy’ archive of past ocean conditions and climate, which has provided a wealth of information about how the Earth’s climate works, and how it has changed in the past.

The work we’re doing to understanding how forams make their shells is important for predicting the future of the marine carbon cycle, and vital to interpret the archives of past climate.

Why Green Island?

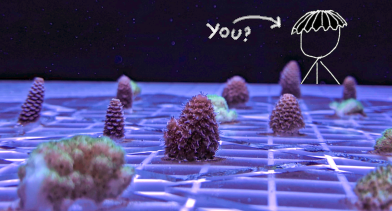

There aren’t many places in the world where you can work with planktic forams. You need a rare combination of easy access to open-ocean water, close to a well-equipped marine lab. Green Island has both!

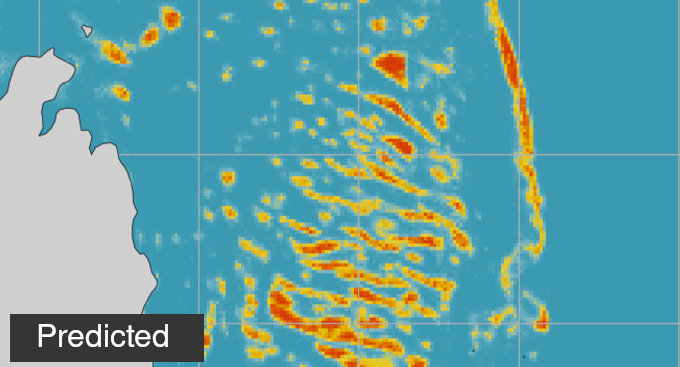

The island sits right in the flow of the Kuroshio current - a fast-flowing ocean current that brings surface ocean water in from pacific and up the east coast of Taiwan, China and eventually to Japan. It’s the Pacific equivalent of the Gulf Stream. This means that the water you find after a 5 min boat ride from Gongguan harbour is very similar to the water you find out in the open Pacific Ocean. The easy access to these types of open ocean conditions is really unique, and makes Green Island a perfect place to work on open ocean plankton like foraminifera.

What are we up to?

The next few weeks will be busy. Each day we head out to collect forams by hand, one at a time while SCUBA diving in the open ocean. We then race back to the lab (which is in an old prison!) to sort them and assign them to experiments while they’re still happy and healthy. Then the daily routine of health checking, feeding and monitoring forams in experiments for the 7-10 days that it takes forams to finish their life cycle in the lab. On this trip we’re focussing on studying the physiology of foram as they produce their shells, and are running experiments to calibrate new proxies for past ocean carbon concentration.