Typhoon Troubles

Over the past week we have experienced many ups and downs on our quest to collect and culture the marine plankton foraminifera.

To Typhoon or not to Typhoon

At the beginning of the week, predicted Typhoon Soala threw a wrench into our collection schedule. We were still able to go out and practice a collection dive before the storm to (literally) learn the ropes, but the rest of the week was a write off. Luckily, the worst of the storm ended up missing the island, but boats were not still allowed to go out for a few days, so we were foram-free for the foreseeable.

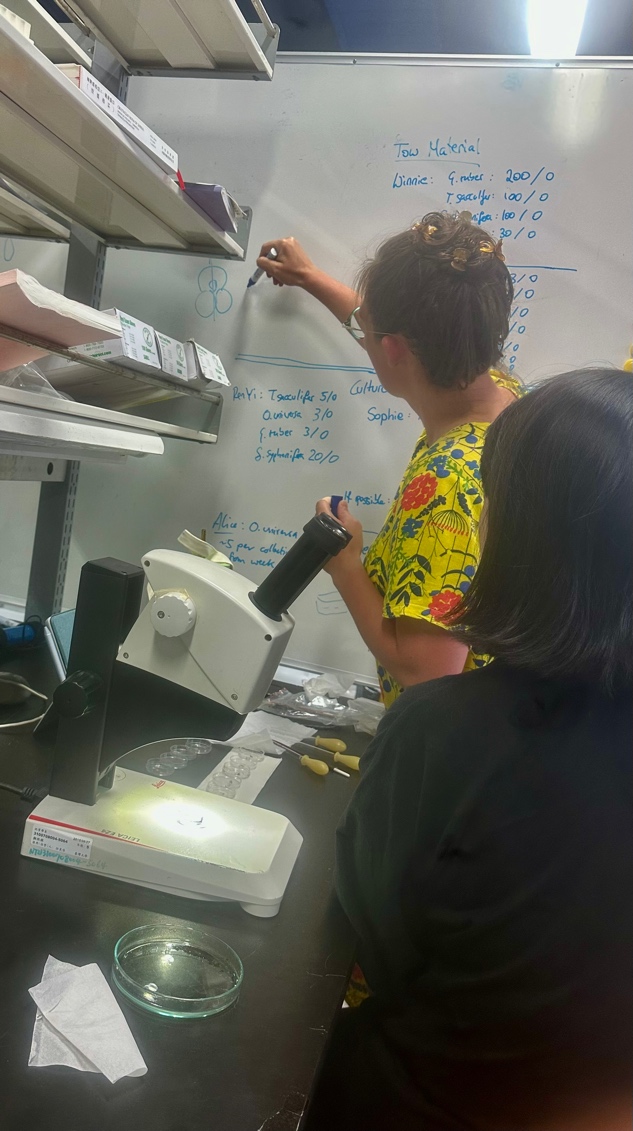

Despite the unpredictable weather, we were still able to prepare for upcoming experiments in the lab, and culture the few forams we had already been able to collect on the practice dive. After collection, forams are examined under an inverted microscope; species are identified, shells measured, the state of symbionts, spines, and any other notable features recorded. Using a wide-mouthed pipette, forams are then carefully transferred from collection jars into culture jars where they’ll live out the rest of their lives (7-10 days) in experiments. Species can be difficult to distinguish, and often a close examination of the shell pores (small holes in the walls) and symmetry is needed. Sometimes, species can only be unambiguously identified later in the life cycle when they have grown another shell chamber.

After Typhoon Soala we were able to venture out into the blue waters again, this time collecting a fair amount of various foram species. Things were looking up as the sun shone, but this was, unfortunately, quite short-lived… A second Typhoon, Haikui, was heading straigh for Green Island. Today this threat became very real as 150km/h winds sent dramatic howls of wind rattling through the lab, and literal buckets of rain were hurled against the lab building. We lost several windows and a couple of roofs in the storm, and there were power and water cuts for the next couple of days. We were the lucky ones - some of the other buildings on the island were reduced to rubble!

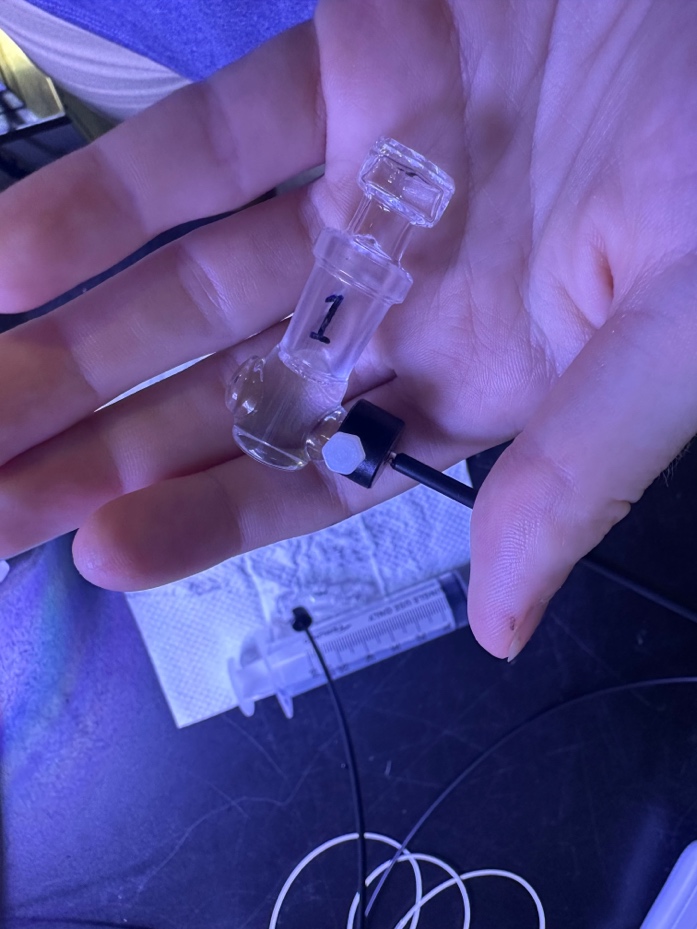

Despite the craziness outside, inside a tiny foram rests peacefully in a tiny glass chamber…

Wrestling with Respirometry

I’ve spent time a lot of time in the lab experimenting with tiny little glass chambers pictured below, in an attempt to develop a method for measuring the respiration and photosynthesis of planktic forams.

For our context, respirometry refers to the measurement of photosynthesis and respiration of an organism. Often it involves placing individuals of the same species in separate transparent ‘chambers’ that contain the organism in a closed system, while inserted sensors will measure the temperature, and oxygen in the chamber over time. If oxygen goes up, the organism is photosynthesising, and if it goes down it’s respiring. You can then control how much light the organism gets to measure the photosynthesis and respiration of the organism. The sensors will usually connect to a computer that displays real-time data of the oxygen production or consumption by the organism, which you can later process to calculate the net photosynthesis, gross photosynthesis, and dark respiration of the organism. All this information gives you an understanding an organism’s response to various ocean conditions, as changes in respiration and photosynthesis rates can sometimes indicate a physiological stress response.

Respirometry is usually done with quite large organisms (e.g. coral colonies, mussels, fish or crabs), but forams are tiny - less than a millimetre in diamter. We’re using specially designed chambers which are small enough (in theory…) to make it possible to measure the respiration and photosynthesis of these tiny organisms. However, theory is only half the picture with this type of experiment, and getting this method working has involved a lot of trial and error to make sure the foram is happy in the chamber, and testing instruments to make sure they’re sensitive enough to measure what the foram is doing inside the chamber.

Respirometry Update: RESP FEST

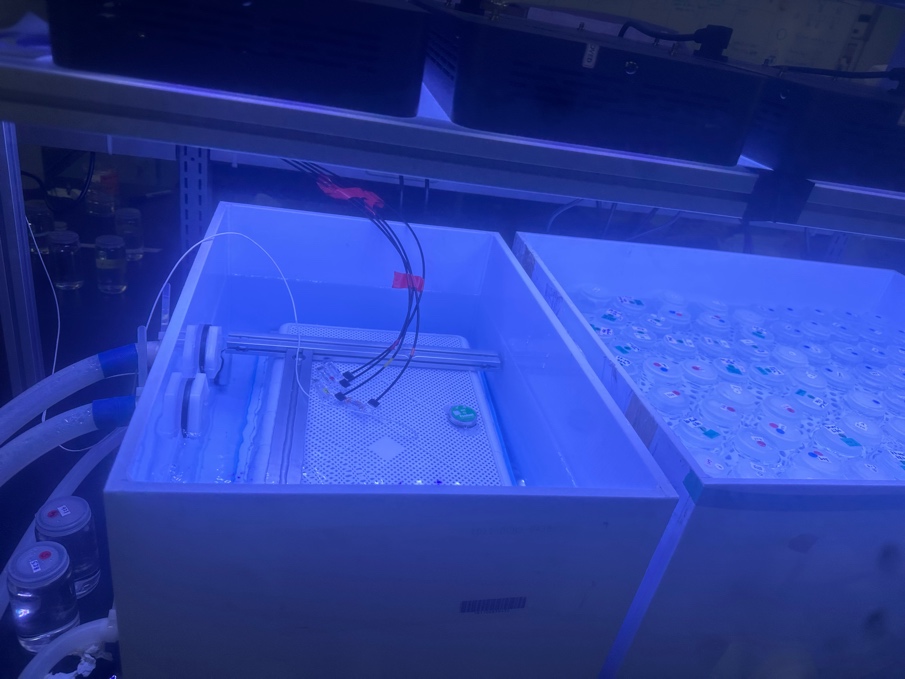

Since I first wrote this post about a week ago, a great deal of respirometry experimentation has been underway in the corner of the lab. RESP FEST, as it has become known, is an all-day respirometry “fest”, with forams as the star performers… more accurately, you might describe this as an ongoing physiological sampling experiment measuring foraminifera oxygen rates throughout the day. From 6 am to 6pm, we have been measuring foram oxygen production, and then for two hours at the end of the day we measure their respiration in the dark, in order to calculate net photosynthesis.

RESP FEST has been quite exhilarating. We’ve refined the technique to a point where the forams are happy for long periods, no bubbles form inside the chamber (which would interfere with the oxygen readings), and are able to mix the chambers to keep oxygen concentrations homogeneous so they can be measured. We’re measuring the same forams throughout the day in order to see if their respiration/photosynthesis rates might follow some type of circadian rhythm. We’re also especially interested in whether a higher concentration of pCO2 in the water would influence foram respiration and photosynthesis rates. There’s been lots of exciting data to chew on, as we charge on into the unknown lives of these tiny bugs!

Irradiant Invertebrates

Amongst the chaos, we’ve still been lucky to find moments to slow down and spend time with spineless sea friends (both spines as in vertebrae, and foram spines!). The fringing reef around Green Island is absolutely breathtaking and teeming with all types of life. A dive below the surface reveals a myriad of curious creatures.

We also encountered the occasional vertebrate…

That’s all for now folks! Wish us luck as we continue the adventure- here’s to hoping for calmer seas and a cooler breeze.